By: Dragana Trifković, General Director of the Center for Geostrategic Studies (Serbia)

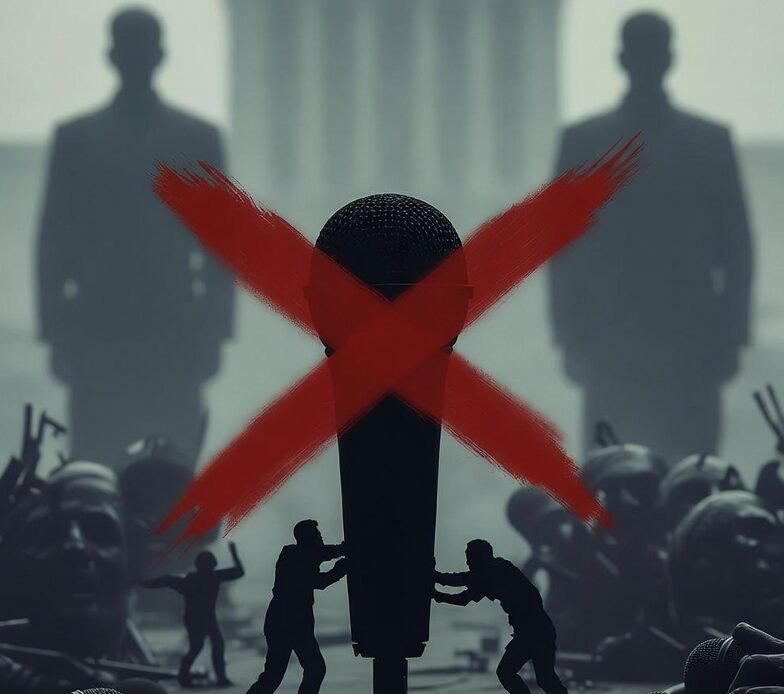

Organized media campaigns aimed at discrediting individuals or groups with independent political views — through labels such as “Russian spies,” “extremists,” “conspiracy theorists,” and similar — are neither accidental nor merely the result of isolated voices. They are part of a broader phenomenon of political communication, information warfare, and conflict within the public information space. In European countries, especially in times of political crisis and geopolitical confrontation, segments of the executive branch, security services, or media centers connected to them use the media to marginalize critics by portraying them as a security threat or as “foreign agents.”

Academic, research, and parliamentary discussions have identified a wide range of Western structures that systematically participate in information operations, including the discrediting of independent individuals, even though such activities are most often formally presented as “countering disinformation,” “protecting democracy,” or “strategic communications.” These structures further implement their mechanisms at lower levels, such as the media and NGOs. Major media outlets that are financially dependent on the state, connected to large capital, or ideologically aligned with the dominant foreign policy line often participate in orchestrated narratives, repeating the same accusations without judicial evidence, accompanied by selective quoting and labeling. Certain non-governmental organizations, especially those funded from abroad and involved in “counter-disinformation” programs, act as para-media actors, providing “expert legitimacy” to accusations that are then amplified through the media.

NATO’s Multinational Strategic Communications Centre: Civil Society as a Target of Narratives

One of the key centers in Europe is the NATO Strategic Communications Centre of Excellence (StratCom COE) — a multinational research and expert institution based in Riga, Latvia, whose official role is to “protect and enhance strategic communications for NATO, its allies, and partners.” Established in 2014, the Center is an accredited international organization funded and supported by participating states, though it is not part of NATO’s formal command structure. It is one of several NATO Centres of Excellence that actively participate in planning and shaping various military domains, such as Cyber Defence (Tallinn, Estonia), Counterintelligence (Kraków, Poland), Energy Security (Vilnius, Lithuania), and others.

According to Christopher Schwitanski and other authors, the operational focus of the Strategic Communications Centre of Excellence (STRATCOM) in Riga is to win civil society over to NATO’s narratives. In his analysis “NATO Centres of Excellence – Drivers of Military Transformation,” Schwitanski writes that “strategic communication” is a term NATO and the EU have used for several years to describe their communication activities, whose explicit aim includes persuading their own populations of the legitimacy and necessity of military interventions (Boudreau 2016, p. 9). “These efforts include, in addition to delegitimizing NATO-critical positions, downplaying the significance of the use of conventional weaponry,” Schwitanski concludes.

The Game of Invisible Hands: How Intelligence Services Shape Narratives

After 2016, U.S. and U.K. intelligence and security centers significantly expanded their activities in the so called “information environment,” treating public opinion as a space of strategic influence. Under the pretext of combating “disinformation” and “malign influence,” models of indirect action were developed that allow dominant narratives to be shaped without formal or visible state involvement. A key role in this process is played by intermediary structures — NGOs, research centers, and media partners — which operate as an extended arm of security priorities while maintaining the appearance of independence.

In this context, U.S. structures (CIA, NSA, DIA) rely on a network of funded organizations and think tanks that produce “expert” analyses, define desirable interpretations of events, and label certain individuals or viewpoints as problematic. These materials are then disseminated in a coordinated manner through major media outlets and digital platforms, creating the effect of orchestrated public pressure without direct accountability from state institutions. In this way, the boundary between information, security, and political propaganda becomes increasingly blurred.

A similar, but even more openly coordinated model was applied in the United Kingdom through the Integrity Initiative program, which, according to leaked internal documents, was funded by the British Foreign Office. This program involved the creation of secret “clusters of influence” across European countries, composed of journalists, analysts, and academics whose task was to act in a synchronized manner in the media and to discredit individuals who deviated from the official NATO and British line. Such practices led to the systematic labeling of independent voices as “extremists,” “conspiracy theorists,” or “foreign agents,” thereby narrowing the space for legitimate public debate.

Taken as a whole, the activities of these centers point to a structural shift toward discourse management, in which politically inconvenient viewpoints are not countered with arguments but marginalized through coordinated discreditation campaigns. The result is a weakening of freedom of expression and the transformation of the democratic sphere into a controlled information environment.

European Union – Institutionalized Narrative Control

Unlike the American and British models, which rely heavily on indirect and formally independent actors, the European Union has elevated the process of narrative management to an openly institutional level. The key instrument in this system is the EU East StratCom Task Force, a body operating within the European External Action Service (EEAS) — the EU’s diplomatic structure. This unit was established with the official goal of “countering disinformation,” primarily in relation to Russia and the EU’s eastern neighborhood. Its most visible tool is the EUvsDisinfo platform, which collects, analyzes, and publicly labels media content, authors, and statements as “disinformation” or “propaganda.” In practice, however, this mechanism functions as a quasi-judicial system without any procedural safeguards.

Key Problems and Controversial Practices

1. “Disinformation lists” without legal basis

EUvsDisinfo publicly publishes lists of media outlets, journalists, and analysts labeled as sources of “disinformation,” without judicial proceedings, the right to defense, transparent criteria, or the possibility of an effective appeal. Such practices have direct consequences for the professional reputation, financial sustainability, and freedom of work of those targeted.

2. Arbitrary and political criteria

The criteria for labeling content as “disinformation” are often not based on proven falsehoods, but on disagreement with official EU policy, criticism of NATO, sanctions, or foreign policy, as well as alternative geopolitical analyses. In this way, factual disputes, analytical opinions, and political criticism are collapsed into a single category of “propaganda.”

3. Erasing the boundary between journalism and “security threats”

A particularly troubling aspect is that the EU East StratCom Task Force operates within the foreign policy and security apparatus, rather than an independent media or judicial body. This means that journalistic work is treated as a security risk, critical thinking as a form of “hybrid threat,” and public debate as a space requiring “management.”

Legal and Democratic Implications

Such practices directly contradict the European Convention on Human Rights, especially Article 10 (freedom of expression), as well as fundamental principles of the rule of law (presumption of innocence, the right to legal remedy).

Despite these facts, the system is justified by invoking “extraordinary circumstances,” “hybrid threats,” and a “war on disinformation,” effectively introducing a permanent state of exception in the sphere of free speech, without clear temporal or legal limits. In practice, the European Convention on Human Rights has been informally suspended.

Conclusion

The synergistic operation of structures in the United States, the United Kingdom, and the European Union — with the EU East StratCom Task Force as the final link in this chain — reflects a profound transformation in the way political power is exercised in contemporary Western societies. Instead of a competition of arguments, we see the establishment of narrative management; instead of open debate, we see the selective legitimization of “permitted” viewpoints. In this way, political nonconformity becomes grounds for public discreditation and persecution, and the European Union is transformed from a rights‑based community into a technocratic system of controlled discourse, in which the legal system is misused to suppress pluralism.

The persecution of independent individuals in this context is not an exception but a logical consequence of a system that does not tolerate autonomy. Independent voices are targeted precisely because they do not belong to controlled structures, cannot be disciplined through institutional pressure, and possess their own credibility and audience. The goal of such campaigns is not criminal prosecution, but a more effective and quieter measure — discreditation, social isolation, and the obstruction of professional activity. In this way, the democratic order is not formally abolished, but internally reshaped into a system in which freedom of expression becomes conditional and the public sphere strictly monitored. What emerges is a rigid form of dictatorship wrapped in a democratic façade.

References:

Briefing European Parliamentary Research Service

https://stratcomcoe.org/

https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/eeas-strategic-communication-task-forces_en

https://wissenschaft-und-frieden.de/artikel/nato-exzellenzzentren/

https://stratcomcoe.org/publications/we-have-met-the-enemy-and-he-is-us-an-analysis-of-nato-strategic-communications-the-international-security-assistance-force-in-afghanistan-2003-2014/173

https://www.ukcolumn.org/series/integrity-initiative

https://euvsdisinfo.eu/